Full Faith and Trust—in Nixon?

Today’s much more relaxing book, though one might not have thought so, is Tom Wicker’s biography of Richard Nixon, One of Us: Richard Nixon and the American Dream (1991) 📚, which has been waiting on my shelf since I was at Fordham. Judging by the bookmark inside I gave it a go poolside in 1996, leaving off just before reading about the 1952 Checkers speech. That speech was extraordinary, if only because it began an expectation of uncommon candor regarding the finances of presidential candidates.

Mr. Sparkman and Mr. Stevenson should come before the American people, as I have, and make a complete financial statement as to their financial history, and if they don’t it will be an admission that they have something to hide. And I think you will agree with me — because, folks, remember, a man that’s to be President of the United States, a man that’s to be Vice President of the United States, must have the confidence of all the people.

How is it that the confidence of all the people is too much to expect these days?

‪Took a break from reading Masha Gessen’s The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin (2012) 📚 to read a bit of Twitter. That was a poor choice for relaxation. Maybe I should make cookiesðŸª

A small person, perhaps a year or two old, toddled by my yard and carefully stooped to pick a beautiful wildflower. Then she and her daddy walked on, as she smelled the sweet dandelion.

Our Elections Make No Sense to Me

I really don’t understand electoral politics, especially the selection of candidates for office and how they are chosen. It’s not the procedure that I don’t understand—that I do—but why certain candidates appeal to anyone enough to garner votes. Why would anyone vote for Donald Trump, for example. Or why would anyone in the Democratic Party think that Joe Biden was anything but a creep?

Similarly, I have an intellectual appreciation for the fact that people vote for their team, but at the same time I don’t know why they would vote for someone they’d never invite over for dinner or let alone with their children. It’s easier for me to understand voting for someone with whom one has substantial disagreements over policy, than it is voting for a liar, a thief, a cheat, a smarmy snake-oil salesman. How can you expect someone to be responsible with government if you can’t trust him any further than you can spit?

Trust matters. Character counts.

Or at least I hope it does. And if it doesn’t, why not?

Perhaps it does and my understanding of character and my reasons for trusting just differ from other folks. I have to presume that people did and do trust Mr. Trump, though I’ve no idea why. It’s easier, I suppose, to believe that your neighbors are misled or deluded rather than to think that they may agree with malicious or callous behavior. It’s easier, but not easy.

Of course, I am most likely missing the big picture here, whatever it is, but I am very tired of being presented every four years with a choice between two people I don’t much care for. Choosing the least unappealing option is not at all satisfactory, like choosing among hung, drawn, or quartered. One wonders if either would win under different circumstances, such as if we ranked preferences or could choose None of the Above. I suspect we have neither of those systems because both the Republicans and the Democrats are quite happy with the current arrangement, unless tweaking the system means their party wins more frequently.

Why Can’t We Have Nice Things?

I’m presently dividing my time between walking, reading John Kenneth Galbraith’s The Affluent Society (1958) 📚, and watching Yes, Minister (1980-1984), in lieu of contemplating the latest shenanigans or burning my phone’s battery on Twitter. The Affluent Society seemed like a reasonable follow-up to Manu Saadia’s excellently optimistic Trekonomics (2016) 📚. I’m enjoying it. Oddly enough the language is not that far off from some of the dialogue in Yes, Minister; it’s almost like there was a certain consistency of schooling or something.

But the questions I’d like answered, in all seriousness and honesty, in plain English, now, today, are “Why not?†Why can’t we have nice things? Why can’t we, in the immortal words of Rodney King, all just get along?

Morning on the Porch in Spring

Woodpecker

Bright yellow forsythia

Sparrow, chickadee

A drop from the gutter

And this bug that alights on my book,

just as I begin to read

The sun warm on my thighs

Provide for … the General welfare

I am livid.

Those fine folks in Congress have an opportunity to help people weather the economic storm caused by COVID-19 and the responses to it, and so the Senate decided that it was more important by far to spend the last week arguing over pet causes and how much pork they could give to favored beneficiaries. And we are supposed to thank them because once again crumbs have been tossed to the masses. Even then presumably respectable Senators like the honorable Ben Sasse of Nebraska were concerned that the unemployment benefits might be too generous and could disturb “the employer/employee relationship.”

Bullshit.

Federal spending is always a decision about values, about what matters, about who matters.

It is never about the money.

The Known Unknown

‪This is the worst game of six degrees of separation ever. Number One Daughter had class with someone who tested positive for COVID-19‬ virus. She has yet to hear if she is to be tested as well. In the meantime, we wait.

She came home from college over the past weekend so that she could be near her people if anything happened. That was joyful. She’s seen and hugged all of her siblings, her mother, me. Made dinner for her siblings and me the first night she was back; a delicious bowl of rice and beans. She’s now at her mother’s house.

What next? Does she quarantine herself in a room far away like a normal teenager, texting for deliveries of food between naps, or mingle with the rest of the households and everybody else with whom she’s already come into contact?

Do I next see her and the others in two weeks, barring any additional symptoms?

It seems prudent, as I mentioned in a post earlier this month, to take precautions in the face of ignorance, not unlike Pascal’s wager on God: We don’t know and the risks are immeasurable. How is this known unknown so much more terrifying than the previously unknown unknown?

A Matter of Life and Death

Here’s a purely hypothetical question for you. Let’s suppose you have a certain number of hospital beds and a certain number of ventilators and a certain number of medical staff. Further, let’s suppose that there are more sick people than there are beds, ventilators, and staff. The system has insufficient capacity to meet the need. Or, in economic terms, demand exceeds supply. How do you determine who receives help?

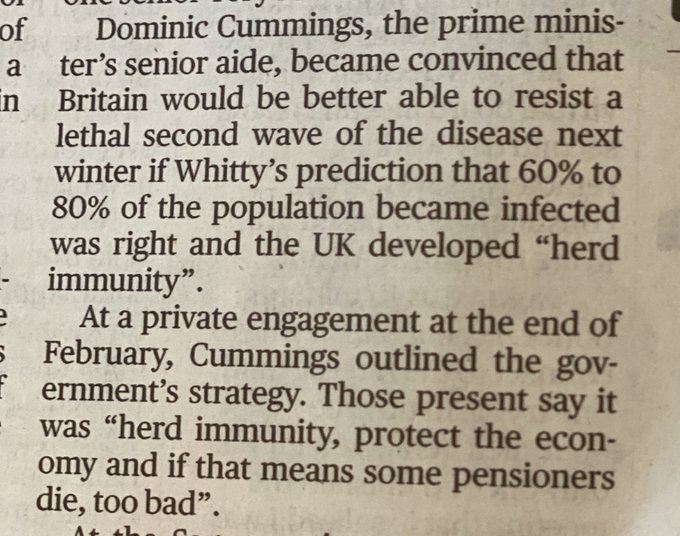

That question of triage, deciding who is to die, is a difficult moral calculus–for some people. For eugenicists or Nazis, it’s not: kill the old and feeble, the physically or mentally deranged, the scum; cull the weak from the herd and improve the species. Or, as Dominic Cummings, aide to Boris Johnson, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, put it: “if that means some pensioners die, too bad.“

Each time the United States argues over a national health care system, someone attempts to assert that socialized medicine leads inevitably to death panels, as if rationing life by one’s ability to pay were more humane than a committee. The thought was that at some point the State would decide it’s just too expensive to keep Granny alive and she would be killed–completely ignoring the fact that Congress funds anything out of nothing more than desire.

Yet somehow refusing to order production of medical equipment or prepare for a pandemic does not rise to the same level of callousness. Somehow seeking to profit from the deaths of thousands is just good business. Those actions cause or exacerbate shortages which lead to deciding who will die.

The response to COVID-19 is in a very real sense a logistics problem, in terms of delivering care to the people who need it. But it’s also one of meeting demand. And in that respect economics can offer some ways to think about it, as the field is, after all, concerned with how finite resources are allocated–the case of surge pricing toilet paper to prevent hoarding comes to mind. Though it seems rather insane for the price of N95-rated masks to have jumped from $0.70 to $7.00 each over the past week, the prices reflect a case of insufficient supply available for the demand. Some people, such as New York’s Governor Andrew Cuomo, redirected existing labor to another task: making hand sanitizer. The Army Corps of Engineers are doing what they do. Others are simply volunteering to help, whether in 3-D printing a valve for a ventilator, or providing patent-free CAD designs, or manufacturing, or sewing.

The response to COVID-19 is also an ethical problem. Most people want to help; the rest are outside society.

R. R. Reno, the editor of First Things, has been on a tear recently. He’s very upset that Roman Catholic churches, among others, suspended public celebration of the Eucharist, and argues that the Church could find other ways of adjusting without shutting out the parishioners. (I suspect he might agree with me about locking the sanctuary doors.) There is something quite magical about gathering together, but expecting others to risk their lives so you can receive the Eucharist seems the opposite of courage in the face of death. Perhaps the Catholic churches could find ways to remain open, but they have decided to help prevent the spread of disease by asking their flock to worship at home, not unlike the early Christians. Some non-denominational churches, more arrogant, won’t raise no pansies.

Mr. Reno also worries about the shrinking of our social life:

[R]estrictions on public gatherings have paused institutional life. There are no Boy Scout meetings, no Little League practices, no Rotary Club or Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. Most book clubs are suspending their evening discussions, even though these small gatherings are permitted. Closed restaurants dissolve informal coffee klatches. Some institutions, organizations, and fellowships will rebound when the draconian limits on social life are lifted. But some will not. And the longer those limits last, the more will wither and fade away.

“Questioning the Shutdown,” R. R. Reno

First Things, March 20, 2020

But over the past few weeks, I’ve seen many people whose first response to the pending isolation was not to buy more toilet paper but to reach out to their family, to their friends, to others they hadn’t spoken with recently; was not to hide under the covers with a flashlight but to arrange online substitutes for in-person discussions. AT&T thanks you. We are a gregarious species.

I am lucky enough to be salaried. I am lucky enough to already work from home. My routine is not disturbed one bit. Except the Spring soccer season is on hold.

Others are not so lucky. Staying home, or, more precisely, away from work, has immediate costs that they cannot recoup. They have no help. The financial situation of many households is precarious. The financial situation of many businesses is precarious, even larger businesses. We are, the bulk of us, over-extended, living hand to mouth. Cash money is, these days, what we need to live. We may adjust to having less. Or we may die.

The financial markets, despite their formerly rosy numbers, are an illusion. The real economy always involves real people, real joy and real suffering, real living and real dying. What are we doing for real people?

We are all looking for a middle ground here, between the Scylla of mass death and the Charybdis of economic apocalypse. At this stage of the crisis, it looks like there is no middle ground. This is an intolerable thing, but it might well be reality.

“The Hard Road Ahead,” Rod Dreher,

The American Conservative, March 20, 2020

Where we devote our attention, where we give our time, and what we spend money on tells us a lot about our priorities. We have choices to make.

Meanwhile, it appears we won’t have to worry about missing Easter services. The President thinks we can open up for business in just a few days.

Vulture Capitalists and Other Scavengers

Remember what happens to the country when the unfit ruler comes to power?

I will make Jerusalem a heap of ruins,

Jeremiah 9:11 (ESV)

a lair of jackals,

and I will make the cities of Judah a desolation,

without inhabitant.

The Plague

Our public library has closed indefinitely, and though I will need to return the large stack of books 📚 I borrowed last month at some point, I do not think I will lack for reading matter if I can manage to tear my eyes away from the slow-moving train wreck that is the world these days: I have many unread books in both the fiction and non-fiction rooms of my own library, which sounds much more grand than it actually is.

This one, however, I’ve read before. According to the receipt inside from Dave’s Comics on Three Chopt Road in Richmond, Virginia, I did so the summer of 1988. It seemed apropos to revisit The Plague.

The language [Rieux] used was that of a man who was sick and tired of the world he lived in—though he had much liking for his fellow men—and had resolved, for his part, to have no truck with injustice and compromises with the truth.

Truth.

Essentially Worthless?

If non-essential work has stopped, and you didn’t enjoy that work, why was it being done?

O Ye of Little Faith

You may have heard this story.

Once there was a devout man who was certain in his faith. All who knew him remarked on his righteousness, for he was constantly thanking God for His great wisdom in making all that was, good or bad.

One day on the evening news this man heard that a terrible storm was coming and that all should evacuate to high ground. “I’ll stay right here,†he said to himself. “The Lord will save me.â€

It began to rain.

It rained so much that the creek rose out of its bed, and waves lapped at the foundation of his house. A neighbor paddled by in his canoe and offered to take the righteous man to high ground. “No, thank you. Don’t worry about me. God will save me.â€

Still it rained, the waters rose, and the man took refuge on his roof. A helicopter hovered overhead, and a National Guardsman swinging from a rope ladder shouted for him to climb up. “No, thank you. Go; help someone else in need. God will save me.â€

Still it rained. And the righteous man drowned.

The man came before God, and asked, “Lord, I’ve been a righteous man all my life. I’ve kept all your commandments. I know in my heart that you are a loving and kind god; I was so sure you would save me. Why did you let me drown?â€

And God answered, “I sent the evening news. I sent your neighbor in his canoe. And I sent the National Guard with a helicopter. What more did you need?â€

Tips for an Advanced Lifestyle; or, Coping with Working from Home

- Wake up you sleepyhead

- Put on some clothes

- Shake up your bed

- Oh, you pretty things, brush your teeth

- Bathe

- Make, eat, and clean up from breakfast

- Lift weights

- Go for a walk

- Do some work

- No! Don’t check e-mail yet! That’s almost as bad as reading the Internet. Wait until you get something done first.

- Eat lunch

- Post a picture on Sad Desk Lunch

- Do more work

- Turn off the computer at the end of the day

The author has been working from home since 2600 baud modems were a thing, but officially only since 2006. The biggest handicap is lack of routine. The second is lack of people. The greatest benefit is flexibility. The greatest hazard is also flexibility. Establish boundaries for yourself and keep them.

Yes, that means a schedule. And pants.

Working from home, often with indefinite externally-imposed demands, will reveal weaknesses in your time management skills. Until the option presents itself, we are not aware of how much someone else’s clock shapes our day. Consider the difference between children during the school year and vacation. Similarly, athletes, musicians, and others may be accustomed to working with a very limited time budget, but what happens when the infinity of 24 hours presents itself? Initially one may have grand plans for the hour(s) of reclaimed time, but those disappear in a haze. Find tricks to divide personal time from that devoted to your work, and work time from that devoted to care for everything else. Some people use pants, others a change of space, and still others a bell.

It will impose, forcefully, on time you once thought was yours: lunch. Meetings will be scheduled to interrupt breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Set limits early. If you are planning to eat with your family, do so. If you formerly took breaks to chat over coffee, continue. Get away from the desk.

It will remove any exercise you may have been getting during your commute. In my case before I began working from home my commute had changed from walking a mile to the train plus several miles to and from the office each day, to a few feet of walking to my car then to my desk. After I began working from home even that little bit of exercise was reduced to the distance from my bed to my couch. Get up and move.

It will beg you to keep going. Don’t.

Stop. Tomorrow is another day.

Update: Consider this a reminder that working away from the home is an invention of the modern, industrial era. Society changes over time.

A Tale of Two Cats

Two cats live with me. One, Lily, is 15; she has been with us since she was weaned, adopted with her brother when my daughters were four and two. Her brother passed away two Christmases ago. The other, Maple, is of indeterminate age, and came to live with us five years ago after she was abandoned. They don’t get along.

Lily used to be the queen, but she’s aged, and now Maple can push her around. As a result, she spends most days on edge, tip-toeing around the sleeping bully. She’ll ask politely for food, stand daintily in second position while she waits, and then not eat–because as soon as a rustle or a can is heard, Maple flops off her chair and gallumphs thunderously to the kitchen, elbows her way past Lily, and quickly consumes all there is, regardless of how much is set out.

Maple is moaning piteously outside right now. She claims to be starving to death. How could I be so cruel as to keep her away from all of her food.

The house has one too many cats.