Darwin Among the Machines (1863)

We take it that when the state of things shall have arrived which we have been above attempting to describe, man will have become to the machine what the horse and the dog are to man.

Darwin Among the Machines (1863)

We take it that when the state of things shall have arrived which we have been above attempting to describe, man will have become to the machine what the horse and the dog are to man.

Sunday, March 31, 2024, The Resurrection of the Lord

Readings: Isaiah 25:6–9, Psalm 118, 1 Corinthians 15:1-28, John 20:1-18

On this first day of the week, in the still quiet before dawn, there’s a Spring chill, perhaps a trifle damp, in the air. The night animals have gone to bed. The cricket orchestra rests. The dawn chorus waits. The Milky Way and the waning gibbous moon, no longer full, light Mary Magdalene’s way through the garden, past daffodils waiting for the first brush of the sun. She had watched Joseph of Arimethea and Nicodemos lay Jesus in the tomb. She had stood at the foot of the cross when he died.

She seen one she loved betrayed, mocked, scorned, tormented, flogged, killed. She had followed him. Where could she be but the depths of despair? But she awoke that morning to come to the garden before dawn.

In Mark and Luke’s telling, Mary Magdalene and the other women came to garden to wash and anoint the body for proper burial, but John does not tell us what she came to do: “The first day of the week cometh Mary Magdalene early, when it was yet dark.” (John 20:1)

There are great thematic cycles in the Bible’s stories of God acting in historical time. Not exact repetition, more like the spiral shell of a Nautilus or a repeating fractal pattern, echoes or ripples. The seasons and feasts of the Church are a reminder that these things happened in time. A slow day-by-day, year-by-year, reminder that they are real — not a fiction, not a binge-watched show where all the time the drama takes collapses together in a tired haze.

This is less explicit in the Presbyterian and Reformed traditions than in, for example, the Anglican and Roman Catholic. Each Sunday, the Lord’s Day, is a celebration of the Resurrection, 52 times a year. Around that basic remembrance of new life, other traditional observances have grown up as further reminders of the story of creation: the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary, Christmas, Advent to prepare for Christmas, Epiphany, Lent to prepare for Easter, this past Holy Week.

The congregation in Anglican and Roman churches actively participates in the reading of the Passion of Christ: we are the crowd. It is we who cry “Save us!” as the Son of David enters Jerusalem. It is we who clamor for his death and demand his crucifixion. We the disciples who can not stay awake. We who flee and abandon him. We who, with Peter, deny we even knew him. We who are guilty.

The memory embodied in these observances ties us back to the beginning of time. When, the timing of a thing, should help us remember. The crucifixion and resurrection happen during the feast of the Passover on purpose. The identification of Jesus as the Paschal lamb is explicit. More than a title, this should draw our attention to the story of the Exodus and the journey to the Promised Land. If you recall, the Hebrews were slaves in Egypt, making bricks and building Pharaoh’s monumental pyramids. The cries of the people rose up to God, and he called Moses to do his work:

When the LORD saw that he turned aside to see, God called to him out of the bush, “Moses, Moses!†And he said, “Here I am.†“Come, I will send you to Pharaoh that you may bring my people, the children of Israel, out of Egypt. … Then you shall say to Pharaoh, ‘Thus says the LORD, Israel is my firstborn son, and I say to you, “Let my son go that he may serve me.†If you refuse to let him go, behold, I will kill your firstborn son.’†((Exodus 3:4,10; 4:22–23 ESV)

It took some encouragement: ten plagues. The first nine would have done for me, but the Lord hardened Pharaoh’s heart. The tenth plague is a whopper:

[4] So Moses said, “Thus says the LORD: ‘About midnight I will go out in the midst of Egypt, [5] and every firstborn in the land of Egypt shall die, from the firstborn of Pharaoh who sits on his throne, even to the firstborn of the slave girl who is behind the handmill, and all the firstborn of the cattle. [6] There shall be a great cry throughout all the land of Egypt, such as there has never been, nor ever will be again.

Exodus 11:4–6 (ESV)

The people of Israel can avoid this devastation, through the sacrifice of a lamb: “the LORD’s Passover. For I will pass through the land of Egypt that night, and I will strike all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, both man and beast; and on all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgments: I am the LORD. The blood shall be a sign for you, on the houses where you are. And when I see the blood, I will pass over you, and no plague will befall you to destroy you, when I strike the land of Egypt.” (Exodus 12:12–13 ESV)

This is not all. The people of the Lord must remember forever. And must forever after sacrifice every firstborn male to the Lord. Their sons they must redeem, or buy back, with a substitute sacrifice. Thus we say, Christ, our Passover Lamb, is sacrificed for us. Christ, the firstborn of all creation, has redeemed his people.

The Exodus did not happen overnight. Before the people of Israel wander forty years in the desert, they had to escape Pharaoh’s revenge. Remember the Passover, we remember the Exodus. Remembering the Exodus, we remember that God saved his people from Pharaoh’s armies with a flood. Remembering the saving flood, we remember that God saved Noah’s family from the capital-F Flood. Remembering that Moses talked with God, and Noah walked with God, we remember Adam and Eve, walking in the garden with God.

And hiding in the garden to their shame.

They — and we — have trouble remembering even with all this structure to help us:

Remember, “You may surely eat of every tree of the garden, [17] but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die.†(Genesis 2:16-17) Remember the Lord your God who brought you out of Egypt. Remember the Sabbath and keep it holy. Do this in remembrance of me.

Our failure to trust goes back to creation, to our time in the garden. God’s constant reminders throughout the Old Testament, and from Jesus in the New, are lost in the onslaught of our enemies, in the depths of our despair, and in the blur of our busyness. We forget. We forget to rest. We forget to trust. We forget God saves, though the reminder is right there in Jesus’s name: Yeshua: God saves.

Let us return to Mary Magdalene crying in the garden at the tomb. What will be in this garden that is not Eden?

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. (John 1:1) And God said, “Let there be light,†and there was light. And there was evening and there was morning, the first day. (Genesis 1:3,5)

“Now on the first day of the week Mary Magdalene came to the tomb early, while it was still dark.” A light breeze rises with the approaching dawn. The birds begin to wake. Mourning doves cry. And the Gardener asks, “Woman, why do you weep? Whom do you seek?”

The true light, which gives light to everyone, was coming into the world. (John 1:9)

Jesus said, “Mary.”

And such joy explodes in her heart. A cry of recognition escapes: “Rabbi!” And, since Mary is not from around here, she smothers Jesus in her arms, enough so he says, “Do not hold on so tightly!” The risen Son is real, solid, flesh Mary can embrace.

And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth. (John 1:14)

Later Thomas will place his finger in the wounds, and cry out in ecstasy and recognition, “My Lord and my God!”

As Henry Wadsworth Longfellow put it in his 1864 poem “Christmas Bells”: “God is not dead, nor doth he sleep.” He lives! Christ is risen! A new dawn, a new creation, has touched the earth that day in the garden. What does this mean?!

The Psalmist writes, “I shall not die, but I shall live and recount the deeds of the Lord. … This is the day that the Lord hath made. Let us rejoice and be glad in it.” The Lord makes every day. This is the day. Today. Now. Let us rejoice! Sing out with joy for we have hope. It is never too late. We can turn from our errors with contrite hearts and find amendment of spirit each day.

“The stone the builders rejected has become the cornerstone.” The builders used their own flawed judgment and rejected the way, the path, the Lord’s law. And yet, now, today, the way, the truth, and the life has become the guide for all our future work, so that whomsoever shall trust in him shall not perish but have eternal life. As the prophet Isaiah writes, “He will swallow up death forever, so that he might save us.” Paul argues in his letter to the Corinthians that the Resurrection has destroyed death, the payment for our sins, the consequences of our disobedience in the first garden.

And if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins.

Good news! We are no longer bound by sin. We are saved through no work of our own. Our help is in the name of the Lord. Full of thankfulness Paul asks in Romans 6:1, “How then shall we live?”

Everyone God addresses by name is given a task. In the garden, Jesus tells Mary, “Go and tell the others.” In the coming days he will give us all the Great Commission: “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age.†(Matthew 28:19–20)

I do not understand how Christ atoned for our sins, the need for his sacrifice, how his death on the cross reconciled us with God, or how it turns God’s wrath from us, but I trust that some day I will. As we sing in the hymn, “Great is thy faithfulness. Great is thy faithfulness. Morning by morning, new mercies I see.” “The steadfast love of the Lord never ceases; his mercies never come to an end; they are new every morning; great is thy faithfulness.” (Lamentations 3:22-23)

How then shall we live? We find our guide in God’s law. And in John 21:12 we find a start:

Jesus said to them, “Come and have breakfast.â€

Sunday, December 24, 2023, the Fourth Sunday of Advent

Readings: Genesis 18:1-15; Luke 1:5-56

Almost from the time the leaves begin to yellow, we begin thinking of the upcoming holidays: All Hallow’s Eve, Thanksgiving, and now Christmas. The individual days may be filled more with work and preparation than with eager expectation, unless one’s a small child, yet this long, extended period feels, to me at least, like the only remaining time of year when everyone is engaged in a shared tradition. And it will suddenly stop on January 2nd, as if exhausted by an orgy of consumption. But for now, Christmas has been in the air — or at least on the radio — for weeks. So many songs telling so many stories: stories of parties and consumption, of gluttony and lust; stories of a young refugee mother on a long journey, arriving late at night, finding no place to stay, exhausted and unwanted, and giving birth in a cold stable.

But what does scripture say?

Much has been left to our imaginations. Two versions are preserved in the canonical Gospels. And like any good tale told around a campfire, each teller tells the story his own way. Matthew takes explicit care to link the nativity with prophecies of a virgin birth, and of origins in Bethlehem, and Egypt, and Nazareth. Luke leaves it to his listeners to connect the dots.

Luke begins, not with Jesus, but with the parents of John, called the Baptist, who prepared the way of the Lord. Listen: this is a story of two women, from the same family, who could not have children. Once upon a time, in the days of Herod, king of Judea, there was a priest named Zechariah. And he had a wife, named Elizabeth. And they were both righteous before God, but they had no child, because Elizabeth was barren, and both were advanced in years.

While Zechariah is alone in the temple, the messenger of God tells him Elizabeth will bear a son. Zechariah recovers quickly from his initial fright, and exclaims, “Inconceivable! I’m an old man, and my wife, she’s no spring chicken either.†The messenger Gabriel is taken aback. He’s given Zechariah the news of a lifetime, and instead of a thank you he’s asked for proof? And so, Zechariah is struck dumb, perhaps both deaf and dumb. And he will remain so “until the day that these things take place … which will be fulfilled in their time.†Incommunicado, he returns home to Elizabeth where, in time, she conceives.

No one else knows.

Elizabeth hid herself. We can presume that few, if any, knew she was pregnant. Even today it’s customary to wait some time before announcing, especially outside the immediate family. Elizabeth, I’m sure, has her suspicions. She hid herself for five months, perhaps out of custom, perhaps because she does not know whether she has conceived or is no longer “in the way of women.â€

Six months after Elizabeth conceives, Gabriel returns. This time to Mary.

Zechariah trembled at the angel’s appearance. The shepherds quaked with fear. And so Gabriel’s first words to them are “Fear not.†Not so with Mary. “Hail, favored one,†he says. Mary’s cool. She’s calm. She’s collected. She’s puzzled, not scared, wondering to herself, “what does that mean?†Mistaking confusion for fear, Gabriel goes on to explain, “Fear not. You have found favor with God. You will bear a son.†Unlike Zechariah, Mary does not ask for proof: she wonders, “How can this be?â€

Gabriel goes into the technical details, then offers a sign: “Your relative Elizabeth in her old age has also conceived a son, and this is the sixth month with her who was called barren. For nothing will be impossible with God.â€

Gabriel paraphrases Genesis, drawing Mary’s attention, and ours, to the founding of the nation of Israel:

Now Abraham and Sarah were old, advanced in years. The way of women had ceased to be with Sarah. So Sarah laughed to herself, saying, “After I am worn out, and my lord is old, shall I have pleasure?†The LORD said to Abraham, “Why did Sarah laugh and say, ‘Shall I indeed bear a child, now that I am old?’ Is anything too hard for the LORD?â€

(Genesis 18:11–14 ; ESV)

Sarah, hearing that she would bear a child, laughed, the sarcastic laugh of “Yeah, right. That’ll happen.†Mary, in contrast, given this extraordinary visit, welcomes it: “Behold, I am the servant of the Lord. Let it be.â€

But then, then she rushes off to visit Elizabeth.

Luke makes no mention of a difficult journey, but of haste. Mary might have been running next door for a missing ingredient at a key moment in her recipe: an ordinary trip. To speculate otherwise, we would have to look outside the Bible, at a map. Luke tells us Gabriel came to Mary in Nazareth. Luke tells us that Joseph and Mary traveled from Nazareth to Bethlehem. (Matthew doesn’t.) Luke tells us that Mary went to the “hill country of Judah†— that is, the area around Jerusalem, which topographically is a lot like the Appalachian Plateau — to visit her aunt Elizabeth. Tradition says Zechariah and Elizabeth lived in Ein Karem, about 5 miles to the west of Jerusalem. Bethlehem is about 5 miles south of both. Each is about 90 miles from Nazareth, up hills and down. The trip is roughly the same, both in distance and terrain, as from Staunton, over Shenandoah and Jack and Allegheny and Cheat mountains to Valley Bend, in the Tygart Valley of West Virginia. Or as if I walked from my house in New York through Connecticut to Massachusetts and back on the Appalachian Trail. So, not exactly next door.

These days our sense of distance and difficulty varies so much from what was usual before the automobile. Unless we walk we have nothing to compare it to. Even when we are familiar with the route, it’s hard for us to imagine Jackson’s army moving from Staunton to McDowell over a day — but they did — much less for us to imagine Mary’s trip in the landscape and circumstances 2,000 years ago in Roman Palestine. It’s almost beyond comprehension the distances people traveled, on a regular basis, without planes, trains, and automobiles. But they did; it just took longer.

I get tired just thinking about it. Earlier this year, Evan and I, along with his Boy Scout troop, hiked up and down a couple of hills in New Hampshire’s Presidential Range — 18 miles, 6,325 feet up and 6,480 feet down — over three days. Our plan was to take the long, steep, scenic route along a creek with multiple waterfalls to the Appalachian Trail above the tree line on the ridge, make our way to the next summit, then rest for the night in an Appalachian Mountain Club hut before heading out to the next two peaks and another hut. I was not prepared at all. Evan had no problem: he’s 17 and fit, not 52 and unfit. I slowed us to a crawl by stopping to admire the view — and breathe.

At the trailhead we had parked next to two young ladies, in their early 20s, one of whom was pregnant, setting off a hike with their infants. I was surprised to find them happily enjoying the hut before us, their children crawling about the place. The next morning they sprinted off up the hill heading south down the trail while we headed north. If memory serves, we met them again in the parking lot, two days later, just as fresh as could be.

So Mary rushes off to visit Elizabeth, where the extraordinary is made plain.

And when Elizabeth heard the greeting of Mary, the baby leaped in her womb. And Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit, and she exclaimed with a loud cry, “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb! And why is this granted to me that the mother of my Lord should come to me? For behold, when the sound of your greeting came to my ears, the baby in my womb leaped for joy. And blessed is she who believed that there would be a fulfillment of what was spoken to her from the Lord.â€

Now, Elizabeth knows she is blessed.

Now, Elizabeth recognizes Mary is blessed.

Now, Mary knows she is blessed.

Before this moment, Elizabeth did not know she was pregnant. Now she knows. Before this moment, Mary did not know. Now she knows.

“And Mary abode with her about three months, and returned to her home.†In three months, after the birth of John, as anyone who can do the math knows, Mary returned to Nazareth three months pregnant, walking another 90 miles, up hill and down. Then did it again, this time to Bethlehem.

The extraordinary thing about the birth of Christ was how ordinary it was. Joseph’s family is from Bethlehem. Mary’s family, Elizabeth’s, is in the next town over, the distance from Monterey to McDowell. What took them all the way to Staunton is unsaid: probably work. The Empire needed them to fill out some paperwork at the Bethlehem office, so they did what one does: stayed with the aunts and uncles and cousins on the small bed in the spare room, upstairs, under the eaves, away from the goats and chickens on the first floor, away from the aunts and uncles and cousins on the main floor. “And while they were there, the time came for her to give birth. And she gave birth to her firstborn son and wrapped him in swaddling cloths and laid him the manger, because there was no space in the spare room.â€

Neither Sarah, nor Elizabeth, nor Mary could bear children. Sarah and Elizabeth because they are too old; Mary because she is unmarried. But they do, and such children! The father of Israel, the Forerunner, the Savior. Neither Sarah, nor Elizabeth, nor Mary could have expected to amount to much.

Just ordinary people.

Ordinary people by whom God did something extraordinary.

Why would God choose them, of all people? Who knows. The idea is so inconceivable we look for reasons and imagine stories to explain away how ordinary they are. Just women, overjoyed they will have children. Just women to whom miracles happened. Our minds rebel at the thought miracles happen to ordinary people. And not just to our modern minds. It’s not enough that God chose Mary, so stories arose that she was conceived by the Holy Spirit to a barren mother; stories that she was not from a poor family or an average family, but to a very wealthy one; stories that she remained forever virgin: extraordinary, not ordinary, fitting man’s idea of the appropriate Mother of God.

But here she is in Luke. Just Mary. Her uniqueness is her unusual calmness when a fierce angel appears, her unusual agreement to be God’s vessel, her unusual normal-ness of rushing off to visit Elizabeth to see if it’s true that Aunt Elizabeth is pregnant, because she is, after all, just an ordinary girl.

The stories we tell matter quite a bit, but we tell stories that help us to understand. And the truth? The truth of it is that God is with us. Not a god only of the rich and powerful. Not a god only of the poor and weak. But the God of all, with us, wherever we are. Such an extraordinary thing, with ordinary people, from an everyday birth, for “the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us.â€

A firm opinion I hold regarding the Church as an institution is that it must be present, be consistent, and be ready to meet people wherever they are. This means open, unlocked doors. This means frequent services, but, just as or more importantly, it means dependable schedules. This means talking to strangers on the train.

Perhaps what most attracted me to the Anglican tradition was the ready-built framework of tradition provided by Thos. Cranmer that not only allows but encourages worship throughout the day, that no only allows but encourages lay participation. Not all parishes have a priest, for those who need one, or a minister of the Word. Not everyone can attend a morning service at 06:00, or a mid-day service at noon, or an evening service at 18:00, or a night service at 21:00. Some, unfortunately, can’t attend Sunday. Some can, but not Sunday morning.

I grew up in what is now a large suburban not-quite-megachurch congregation, but we moved and I spent my teen years in a tiny one. A tiny one of the four churches that Dad served. His time was divided; but whether they had a sermon or not, they came together to worship each week.

So I’m puzzled when churches pull back, reduce their hours, close their doors.

How can anyone find you then?

It’s not unlike scheduling any other meeting. The more people you have, the harder it is to pick a time convenient to everyone, and the more the need to just pick a time and shrug one’s shoulders about those who will miss out. This may work for presentations from Human Resources, or an academic conference, or the World Series, but the Good News is unlimited. God does not fit in that one convenient hour once a week.

God is patient. He waits.

For three months now I’ve been leading Morning Prayer at 07:30. At most there are three of us, usually just two, sometimes one. We should probably announce it more loudly. Anyone could lead a noon service. Anyone could lead an evening one. When I move to that town, I will.

Beware this trap.

I’ve been in congregations of varying size, the largest of which was Catholic. The second largest of which was located at the intersection of I-71, I-275, and Fields-Ertel Rd., and sold its property to finance growth. The smallest congregation I was adjacent to was two people. Those two old folks kept the building in tip-top shape until they passed and it was sold–to, of all people, Episcopalians.

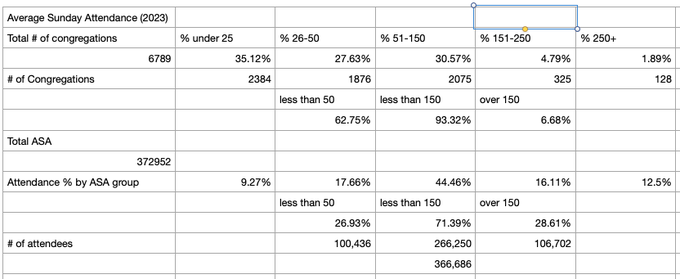

If we were to retire all churches with fewer than 50 attendees, we would close more than half, including all in Alaska, though not the two in Micronesia.

If those with fewer than 150, then 93% of all congregations, 71% of all attendees.

The first reason this does not work is that Episcopalians were thin on the ground before they started declining. The decline was coincident with certain changes in practice if not in doctrine, but was presaged by events in other denominations. Some folks might like to blame it entirely on Bishops Pike and Spong; they were accelerants, not a cause.

tl;dr: It’s the Boomers.

The participation rate in church attendance during the middle of the 20th Century was absurdly abnormal. This is due to a couple of reasons, the major ones being not having to work on Sunday, lots of kids, and disorganized sports. We’re dealing with the decline from all of these.

It is no coincidence that the decline in church attendance aligns with the advent of the Rust Belt and the Me Generation’s adolescence, but not for the reasons that all of the fancy people think. It’s only because of 1) economics and 2) adolescence.

In the meantime, the church has been chasing phantoms trying to entice the past three generations of rebellious adolescents to come inside by being cool, and in the process has lost itself. It did not help that earlier in the century most denominations sided with the Modernists.

They became subject to the whims and chances of fate: poll-driven, not unlike the waffler Bill Clinton. So that now they resemble nothing more than another press office for whatever progressive politics cares about this week.

How could that possibly attract anyone, much less cynical youth? They may as well join the Democratic Party or a world-saving, money-grabbing NGO and get their religion from the source.

So, what to do? The parish is critical. Centralization of the physical presence of the church will not work. It will only hasten the decline, for two reasons: 1) it increases the cost of attendance for those who are already attending, and 2) doesn’t address the core problem. It addresses neither doctrine, nor general economic failure, nor the built environment, nor why people move from one place to another. It assumes that we will continue to subsidize large houses and large cars and cheap gas. It assumes congregants have both cash and time.

The middle of the 20th Century was a once-in-a-lifetime event, equivalent to the end of the Black Death in Europe. It has been been obvious for decades that it can’t go on, but we have not changed our behavior one whit.

So what might work? The Rev. Crosby notes an area of expenditure which sucks funds from the work of the church: administrative staff. I’ve not looked at the numbers for the Protestant Episcopal Church of the United States, but the balance in the Church of England is out of whack. Redressing this may entail not being active in random social programs.

One thing which may help local parishes is paying for the livings of clerical staff from the central fund. On the one hand, this would allow distributing staff where needed. On the other, we’re currently in the red due to the assessed contribution to the general fund. See above. Along those lines, one reason clergy need $$ is because of debt. Which brings us to the seminaries. I would prefer they be orthodox, but whether they are or not, postulants should not be saddled with debt and years of waiting before engaging in pastoral work.

Orthodoxy, however, is critical. The Gospel is the reason the Church exists. Without preaching the Gospel, what is the point? Thus, catechesis is as important as evangelism. Teach the people already there. Then spread the news.

All of that is well and good, but we need children. They come back after adolescence, if the church is still there and treated them well. Not all return, but some, perhaps most. And to get children we need to marry men and women. Pragmatic utilitarianism, if the outright injunctions and prescriptions in the Bible won’t, requires that the Church insist that marriages be between men and women and result in children.

Our congregants left. Some have died. Where did they go? Do they play travel soccer on Sunday? Are they working at Walmart? Did they get the hell out of Dodge? If the latter, does that destination have a congregation for them? If it’s a schedule conflict, how can help that? We can, by being ready and waiting, generous and available. But, we do need to realize that barring extraordinarily well-distributed economic prosperity, the church’s natural membership rate is closer to 20% than it is to 60%.

There’s a certain amount of money necessary to keep things afloat. Roofs need repair every now and again. And the congregants do like heat in the winter. And ministers of the Word should be free of worldly care and concern. But income inequality is outside of our direct control: unless of course, one is a believer, a banker, and in a position to effect change. The widow’s mite must sustain us.

The polities of some denominations do not scale as well as others. Some are limited by their view of the sacraments and who can deliver them. Some by what education is required of the minister. Some by who exactly can be ordained. Some are not. It is for these reasons that there are more Baptists and Methodists than there are Presbyterians and Anglicans. And so depending on the denomination there are different logistical considerations which must be taken into account, unless one wants to change one’s polity.

Using statistics to make decisions, rather than simply inform them, can lead one astray. This is true whether one is a church or a Fortune 100 company. Arbitrary cut-offs cause lying.

But more critically, I suppose, they cause one to abandon one’s mission.

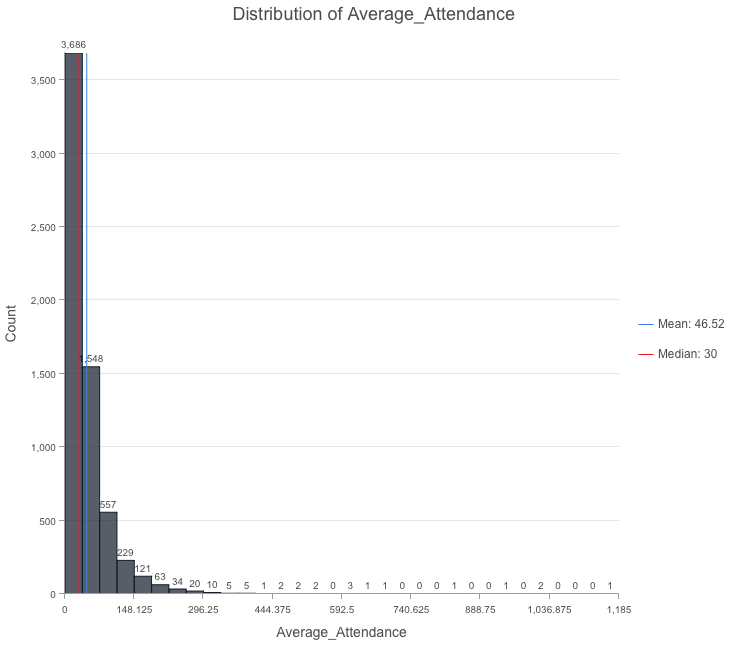

I will use Average Sunday Attendance (ASA) <150 as the cutoff in the example below, since there are few congregations between 100 and 150 in average Sunday attendance and I don’t have the full 2022 dataset. See the histogram for 2021 below.

If we were to retire all churches with fewer than 50 attendees, we would close more than half, including all in Alaska, though not the two in Micronesia. If those with fewer than 150, then 93% of all congregations, 71% of all attendees, or 366,686 of the 372,952 who come to church.

Thus very effectively pivoting to video.

Church membership, like almost everything, is a Pareto distribution.

I would like to thank Rev. @benjamindcrosby for starting this discussion. If it were not for thoughtful, concerned clergy like him, this church would stagger blindly over the cliff, wondering all the time why pews were empty while event rental revenue wasn’t making up the slack.

And I would like to thank @iamepiscopalian, because it has offered a refuge for those who have not fled God but who need shelter from the works of men. Though we differ on essential matters, Articles of Religion XXVI still pertains. More theologically, it is not the building but the people who are the church, and where two or three are gathered together, so shall Christ be.

Sunday, September 10, the 15th Sunday after Pentecost

Readings: Ezekiel, 33:7-11; Psalm 119:33–40; Romans 13:8-14; Matthew 18:11-22

Peter has no questions about who is his brother. But he wants clarification. How often shall I forgive my brother? Jesus replies: constantly.

But I have questions! Who is my brother? I must make sense of this to make sense of the passage. Because Jesus also says to let your brother go and treat him as someone from another tribe or a tax collector. So many questions! Who is my brother? I should treat my brother as a Yankee or revenuer? But wasn’t Matthew a tax collector? What does he mean we hold the keys to heaven? How do we constantly forgive? We just cast our brother out!

The first question is relatively easy to answer: Jesus tells us.

And stretching out his hand toward his disciples, he said, “Here are my mother and my brothers! For whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother.†(Matthew 12:49-50)

Those who trust in him as the way, the truth, and the life. Those who repent of their sin and follow him. These are the children of God. Paul talks about this all the time, as in Romans 8:14–17:

For all who are led by the Spirit of God are sons of God. For you did not receive the spirit of slavery to fall back into fear, but you have received the Spirit of adoption as sons, by whom we cry, “Abba! Father!†The Spirit himself bears witness with our spirit that we are children of God, and if children, then heirs—heirs of God and fellow heirs with Christ, provided we suffer with him in order that we may also be glorified with him.

Who is my neighbor? He tells us this too, in the parable of the Samaritan. But that is not the question today. Today we ask, who is my brother? Each member of the Church is.

So. We are children of the same family and as siblings do, we fight.

When my brother wrongs me, what should I do?

Have you held a grudge against your brother or sister for so long that you have not spoken to them in years? Why? Was that cause worth it? It seemed so at the time, yes?

Jesus tells me to repent and seek forgiveness if I have wronged my brother.

So if you are offering your gift at the altar and there remember that your brother has something against you, leave your gift there before the altar and go. First be reconciled to your brother, and then come and offer your gift. (Matthew 5:23–24)

My broken relationship with him harms my relationship with God. I must imagine it saddens God. One of the great joys of my life is hearing my children laugh together. And the great sadness is like it: when they sneer and scowl and blame.

Today Jesus tells us go, seek to reconcile with your brother who has wronged you. Our brother might not ask for forgiveness; we should ask him. The burden is on each of us to restore our relationships. This is a tough charge from our God. He asks us to swallow our pride and seek forgiveness for our wrongs. He asks us to swallow our pride and forgive those who have wronged us.

Can we do that? It seems impossible. It is impossible. How could we even?

We can, with God’s help.

And so we have been given a procedure to help order our relationships. Our Presbyterian Church takes this particular injunction fairly seriously. It is in the historic Reformed confessions, in the Heidelberg Catechism, the Westminster Confession, and others. And it is reflected in the method of discipline in the Book of Order, however infrequently used.

Notice in our own families how divisions start. One person does something stupid. Another may become annoyed and stop talking to the others. We seek allies, we gossip or slander, and the offensive party is cut off. No more invitations to Thanksgiving dinner. No more Christmas gifts. No more wedding invitations. It’s a strong power, cutting someone off from the family.

We are given almost the same procedure. The difference being loving-kindness instead of spite. We go seeking reconciliation, not dominance. We should approach our brother, or our sister, with compassion and tenderness, in humility, not swollen by an overweening righteousness. Not because we were wrong, but because separation is sorrowful.

Jesus says, try once alone; try again with witnesses; try again with the community. And if that fails, you did your best: let them be on the outside. And this has consequences.

That is what is meant by the keys of heaven. God’s family, the adopted children of God, will join him in Heaven. And if one is separated from the family, how then could they join God in Heaven? As night follows day, actions have consequences, on earth as it is in heaven.

But the instruction does not end with a permanent separation. What ends are our attempts to reach out to our brother. For recall it is on both of us to repair the breach. We have done our part, and now his relationship with us and with God is no longer our concern. It is his.

As Ezekiel puts it,

But if you warn the wicked to turn from his way, … you will have delivered your soul.

What never ends is our responsibility to welcome him back.

Can we do that? It seems impossible.

We can, with God’s help.

God wants his whole family. That is why the Shepherd comes to find us. It is not through our efforts that any of us are saved. Only through God’s grace alone. We are lost, and cry out.

God continues to look for his lost sheep. He is patient, and steadfast in the search. Longing desperately, as the parent of a runaway child longs, to welcome us home again if only we return. You recall the parable of the prodigal son? The prodigal son, like us, has frivolously spent his trust fund. He has nowhere else to turn, and heads home, willing to do anything to regain the smallest favor. The lament of Israel in Ezekiel might be his:

“Our transgressions and sins weigh upon us, and we waste away because of them; how then can we live?â€

“I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked,†says God. “Turn back. Turn back!â€

Reach out to the hand of God and he will pull you in. He is there waiting.

Jesus called Peter to walk to him across the water but Peter lost faith and sank. But Jesus plucked him right out. God does this throughout the Bible, from Genesis on. He created man and woman in his image, gave them the will necessary to take care of the garden, but we, as children do, did not listen. For God so loved the world, he made a covenant with Adam, with Noah, with Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, David — all leading to Christ. God inserted himself in the world and time to sacrifice himself for us.

I admit: I do not understand this mystery.

There was a time I may have come close: the night home from the hospital after my first daughter was born. She didn’t quite want to sleep, so I walked this tiny bundle around and around in the circle of moonlight on the living room floor until she relaxed into a heavy weight on my shoulder. And of a sudden I was overcome. I had no words, no way to say what I felt, except “for god so loved the world.†How could it even be possible to love something so much more than this? That moment, holding my child, I thought I understood. I would give anything for her.

This is why it’s such a puzzle that God gives his Son for the world. Until we recall the Trinity, and realize God gave Himself.

In response our duty is to accept God’s grace, repent of our sins, and spread the Good News. But if the one who hears does not listen, what more can we do? If the one who has heard will not repent, what more can we do? We are only human, after all, born to make mistakes.

And when shall we respond to God? When shall we respond to God’s sacrifice? Now. Now is the moment to wake from sleep. Now is the time to lay aside the works of darkness and put on the armor of light.

As the Psalmist says: Give me understanding. Lead me. Turn my heart. Turn my eyes. Confirm your promise.

How then shall we live? Honorably, as in the day. Gratify not the desires of your flesh. But go to your brother whom you have wronged, go to your brother who has wronged you. Reconcile yourselves. And live together as children in the beloved family of God.

From 1850 to 1946, the U.S. Census counted religious communities and structures. If one is aware of the history of the 20th Century, and the role played by Hollerith’s machines in that history, what other option was there than to stop counting after the war? Besides, it might be impolite.

There are many reasons people look at these numbers, but one is “Why is my church shrinking?†This is not the same question as “Why is my church declining?â€

Generally speaking, the answer to the former is twofold, and does not involve theological arguments: transportation and demographics. People have cars. People left your town. And your congregation isn’t having children. (As just one example, in 1970, the Sunday School at Grace Episcopal Church, Millbrook, NY, had 100 children enrolled; in 2023, it has 4, more or less.)Â

The answer to the latter includes the former, but also the distribution of wealth. In particular cases it may include theology and practice.

The Census data conveniently allows us to expand our statistical view of religious practice beyond the last few decades given in most graphs. And so here are local organizations and edifices as a rate of the population.

Americans rapidly formed new religious communities and built physical homes for them between 1870 and 1900 — the number of congregations and buildings more than doubled between 1870 and 1890—yet by 1930 the proportion of each relative to the population was roughly the same as in 1850. Notably, the above does not show individual persons, but buildings and congregations, so we cannot estimate the size of these congregations. Many of the structures remain and architectural historians could provide an estimate of seating capacity. However, the Census also reported membership from 1890 to 1936, and compiled membership numbers provided by other sources thereafter, so we’ll just use those. In 1890, 34% of the population was a member of a religious body. By 1920, 51% were. This dropped slightly during the roaring Twenties, but by 1960 was up to 64%. By 2020, this was 49% — which is low only by comparison with 1960.

Assuming the accuracy of the data. The Census notes that “data presented are not directly comparable from census period to census period.†Where they overlap, these numbers contrast sharply with those from the Yearbook. The ARDA numbers don’t overlap. And there’s a large 15% gap between 1970 Census numbers and 1980 ARDA numbers, which probably reflects the different survey methods.

So, how many people per congregation is that? On average, 131 members per congregation in 1890, to 452 per congregation today, down from a peak of 622 in 1970. But that’s an average. A dive into the statistics of a given body would show Pareto’s long-tailed curve: many tiny churches, a few enormous. However, we can safely surmise that there are fewer, larger churches now than in the past. Why? Because the number of congregations as a rate of the population is lower, yet the average size is higher.

—

Sources:

I’ve been thinking about this verse from Sunday, and particularly about “while it was still dark,” as the preacher attempted to make a point about the depths of despair.

Now on the first day of the week Mary Magdalene came to the tomb early, while it was still dark, and saw that the stone had been taken away from the tomb.

John 20:1 (ESV)

Or, as the hymn has it, “while the dew was still on the roses.”

On Maunday Thursday, the first day of Pesach, the moon was full. By Easter Sunday, the waning gibbous moon was still quite bright, so “while it was still dark” was not that dark. And even with a New Moon the sky was somewhat like this photograph of the Milky Way, taken in the Negev.

And the garden somewhat like this, depending on what is meant by σκοτίας ἔτι οὔσης. I like to think the author meant 04:00. The silent time. The night animals have gone to sleep and the birds have yet to sing.

Metaphorically, dark. Yet a world beautiful and good.

Go out early, just before dawn, smell the world in Spring and listen.

Wait.

Something is about to happen.

Climbed the fire tower on Sounding Knob with some of my children this morning, and after overcoming the vertigo looked out over the oldest mountains in the world.

And one of the oldest volcanoes.

Good piece by Sohrab Ahmari in the New York Times today. (Shame he blocked me on Tweeter after I suggested he might be an idiot for all the shilling he did for Trump. He’s not a moron, usually, but did play one for the New York Post.)

Opinion | Why the Red Wave Didn’t Materialize

Fake G.O.P. populism challenged “woke capital†— companies that it believed had become overly politically correct — but didn’t dare touch the power of corporate America to coerce workers and consumers, or the power of private equity and hedge funds to hollow out the real economy, which employs workers for useful products and services — or used to, anyway. The Republican Party remained as hostile as ever to collective bargaining as a new wave of labor militancy swept the private economy.

Republican economic policy remains overwhelmingly beholden to a donor class of plutocrats and high corporate managers. Seen from that perspective, it makes sense for the party to talk about adjuncts and baristas as though they were members of the ruling class. In doing so, these faux populists can remain indifferent to issues like wages and workplace power, health care and the depredations of speculative finance.

On Tuesday, it seems enough members of the “the multiracial working class†may have decided to repay that hostility and help deny Republicans their red wave: either by staying home or casting their ballots for the party that, despite its other failings, keeps entitlements inviolate, supports collective bargaining and has sought to ease the student-loan burden. Boo Hoo!

All of his observations may be equally applied to the Democratic Party. Both are controlled by an oligarchical plutocracy who struggle, for some definitions of struggle, with how they might pretend to be of the people and for the people without actually giving much attention to the people. Despite that, the Biden administration has somehow managed to begin reining in some of the excessive behavior of that class, in a slow, either half-hearted or deliberate depending on your perspective, fashion.

This does not so much make the Democrats a better party than the Republicans, as one which has at least read The Dictators Handbook and is throwing the dogs a bone.

One humid summer night, passing through Maryland on a long road trip, I stopped for gas and a pack of smokes. In those days gas stations weren’t often open at all hours; when they were, they were lonely and alone—and often still are, off the beaten path.

I once was able to escape entirely into books, and could leave the world behind until one was done, no matter the troubles troubling my heart. My brother, a mere 15 months younger than I, crumpled his Miata this morning, and lies unconscious with a not-entirely-fractured neck in a hospital in Virginia, while I am here in New York in front of a computer.

So close in age, we were fairly inseparable until those horrible years of the mid-teens where one cuts all ties. We wrestled. We fought. We played Little League baseball together. He was Tom Seaver. I was Johnny Bench. We were in Scouts together. We put away folding chairs after church events together. We snuck out of the service and ran around the building. We tried drinking coffee. We helped Mom in the food pantry together. We rode our bikes around town and gave little old ladies heart attacks with our daring street crossings together. We mowed lawns together, then rode those bikes and bought comic books, chili dogs, and cream soda together. He would grow up to be a police officer and I would be a fireman. Or maybe we would both be Millionaire Super-heroes. We made Big Plans for our Secret Lair under the mountain where he’d have a bedroom near the underground hanger and I’d have one near the boat dock on the hidden river. We read The Hardy Boys’ Handbook: Seven Stories of Survival, and plotted all of our adventures in Great Detail.

Everyone thought we were twins. Life as an adult without him was unimaginable.

Then I withdrew into myself in high school, went away to college, got married, and we drifted.

Three weeks ago I was in Virginia riding in that Miata with him, thinking about the Hardy Boys, off on an adventure.

On Marketplace last night, Kai Ryssdal stated the unspoken obvious: “Guns are a business. A big business multi-billion dollar business in this country.â€

I’m reminded of an epigraph from Myth Adventures:

War may be Hell, but it sure is good for business.

The Association of Merchants, Manufacturers, and Morticians

When will life become more profitable than death?

This here book I’m reading is older than I am, but just by a hair. It was checked out four times before I was born; the last just in time.

It remained popular through 1972, then interest slowed. Perhaps everyone had read it by then, or they were watching the continuing story on television. Interest picked up a bit in 1986, or someone took real long to read these 109 pages. But who can say, other than the librarian, if I’m the first to have read it since July 15, 1995?

It was 18:30 just a few minutes ago and the sun had no thought yet of setting. Now it’s black out, and my computer woke up to tell me it is going to sleep. “Where does the time go?†the lady asks. I’ve no clock here telling of those inexorable seconds ticking off each moment.

Ten years ago I would have said I’d lost the time to online media. Today, though, no. It’s been raining and I’ve been sitting here listening to the rain and, every now and again, thinking. Three hours seemed like forever so long ago. Today? Just a moment lost in thought, like tears in the rain.

Luna, the smallest and youngest of our cats, has in her short time here cornered two snakes behind a door in the basement. And somehow she climbs the concrete wall in the laundry room to look into a gap in the framing.

On the wire shelf above the clothes washing robot, wrapped over and under the wires, is a shed skin.

Today she found the third.

This is Luna. She is so threatening.

Number One Daughter graduates from SUNY New Paltz tomorrow. What next for her?

Number Two Daughter has returned home from for the Summer and is between plans. I do not wash my dishes frequently enough for her; a household of three barely fills the dishwashing robot while a household of four produces more than enough, so some wait on the counter for the robot’s human helpers to put away the previous load. She has taken it upon herself to make the sink to her liking. Perhaps also now she is home her fish tank of snails will move to her room: the electrical water pump is louder than my tinnitus, and drones away the quiet.

Dense fog, low clouds cover the hills; not much beyond the road is visible. The birds don’t mind; they keep up their morning chatter. They like this cool morning. At the house next door the laborers have raised a ladder. They like this cool morning too. The National Weather Service warns me that there is dense fog.

They also warn me that after noon today until tomorrow’s night an oppressively hot and humid heat will hang over the young students and their families sitting on the lawn in front of the Old Main Building. New Paltz’s gowns are a bright blue, but still not the sort of thing one wants to swelter in while a notable figure sends them off into the world to do Great Things.

I barely recall my own commencement 29 years ago. It was sunny. It was hot. It was long. My family was there, somewhere behind me, on folding chairs. We were exhorted, by multiple speakers. I shook a hand. I went off into the world to do Great Things.

One of those Great Things is graduating from SUNY New Paltz tomorrow.

Strong breeze tonight

Warm breeze tonight

Low breeze tonight

The clouds above, unmoved

The stars above, unmoved

The dipper above, unmoved

This breeze, low, around

the ground

tonight

This breeze, low, around

my crown

tonight

Toward the end of March 2020, searching the Internet for some solace, I found myself watching the Dean of Canterbury’s morning prayers. A week or so later, it had become a daily practice for the cats and me to join in these prayers both morning and evening. I told everyone I knew and loved. Some made this their practice as well.

By canon law, Dean Robert Willis must retire on his 75th birthday, which is this coming Tuesday. I will miss how he seamlessly tied the Psalm and the daily lesson together with anniversaries of the day and current events. And I will miss the comfort of his voice.

But I will continue the daily practice.

Thursday afternoon the frogs who cling to the trees nearby gave voice to their mating song. A few daring fellows first, by evening constant singing rose from the woods surrounding the soccer field amphitheater. Tonight the humid airs are theirs.

Humid out, but cooler than inside, so I’ve opened the windows to let in their song.

The virtual world cannot compare. It engages but one of our senses, and even that just barely. How sad, how deficient must those be who think such a pale imitation could be even marginally attractive? Even the makers of amusement park rides are not so foolish.

I spread the herbed chèvre on sourdough flatbread, then marvel at the flavors on my tongue. Can your masturbatory fantasy machine do this? Why should it, when there is grass, basil, oregano, and goats?